WHITE LIFE COUNTS MORE

Photos & text: Eliza Kowalczyk

Interview with Paulina Bownik, a doctor helping refugees on the Polish-Belarusian border - December 13, 2022

E.K.: Since when are you involved in the crisis on the Polish-Belarusian border? And what are you doing?

P.B.: I have been involved since Usnarz Górny, when I received a message that there are 30 Afghans there, some of whom need medical attention but I was not allowed near these people. Parallel to them, other groups of refugees passed through Usnarz Górny on other sections of the border. Generally, I try to make those people who are in the forest suffer less. This is one of my primary tasks because these people are in the woods in pain. My second primary job is that these people are able to move on. A man left in a Polish forest is sentenced to death. If someone is hypothermic, for example, or severely dehydrated, these are life-threatening conditions. I think these are the most serious threats in winter and summer. In winter, we deal more with hypothermia, while in summer, when it was hot, we dealt with people so severely dehydrated that they had hallucinations. A person who is already in the second stage of hypothermia is already falling into lethargy, nothing matters to him, he stops walking, and as a consequence, he may die. Similarly, a person who has orthopedic problems, and now I have a lot of them. People fall off the fence and break. A person who has broken a leg or even sprained an ankle or even let's assume a dislocated shoulder joint - has impaired mobility and there is a high risk that it will lie in some place in the forest and this is death for it.

E.K.: What difference do you see before and after erecting a 5.5 meter fence? What has changed, how was it before and how is it now?

P.B.: It's definitely harder. The difference may not be as big as reported by the Border Guards, but there are definitely fewer crossings. However, when it comes to the condition of refugees, as I mentioned, there are simply more orthopedic problems, i.e. all kinds of fractures, sprains, tendon ruptures (read also an interview with Kasia P. a volunteer who helps refugees placed in a hospital). I can't really diagnose it either. I'm not an orthopedist. I guess even if I had a doctorate in orthopedics, I don't have x-ray eyes. Recently, I visited a man who fell on his heels, his foot was very swollen, but he had pain in the shin area and the foot was bent without any mobility. He probably had a broken tibia or fibula or both, but I can't tell in the woods. In these cases, I have to assume the worst case scenario, assume there's a fracture, give the man a brace, give him anticoagulants.

E.K.: Is there anything you're afraid of about this crisis, about what's going on? Is there anything that bothers you?

P.B.: At the moment, when it comes to medical facilities, I am in a much better position than a year ago, because large international organizations have joined. One of them that I can mention is INTERSOS. I can't speak about the second one because they don’t want to be mentioned. And at the moment I am an emergency medic who goes to the forest when others cannot, when there is a gap. Therefore, I am not in such a state of permanent readiness as I was a year ago. A year ago, I was afraid of many things. And yes, I also had less experience. I was afraid that, for example, I would be called directly from my shift, tired, driving 80 kilometers ahead and I would hit a tree. I was afraid of these medical calls. I don't have a degree in emergency medicine, so I did things that internists don't do. I've done venipuncture, I've had women with miscarriages. I didn't know whether to examine them gynecologically or not. Sometimes you have to make difficult decisions, because after a miscarriage a woman should be given such drugs to cleanse the uterine cavity, to give birth to the placenta. You had to decide whether it was safe in the forest at all? What was the most burdensome for me, were the children in the forest. It's always been difficult. As for now, I feel supported by organizations that are here and I hope they will stay. I don't feel alone anymore.

E.K.: But you did feel alone?

P.B.: Yes, I mean, I think I'm probably the only person who has partly resigned from her job. All doctors in Poland work at least two full-time jobs, which is really very little. Most of us work 3-4 jobs and I left my two jobs to be able to help here. As far as I know, I don't think I know another person who simply left their jobs and their activities to be available here. This absolutely does not mean that other people did not come here and did not help. I always emphasize that maybe I was just that kind of person, maybe.

E.K.: Do you see any solution to this border situation at all? Because we thought it would end with this wall. Well, that hasn't changed. People in the forest are freezing. As you say, not only hypothermia in winter, dehydration in summer, but now these orthopedic injuries have arrived. What is the solution to these people's situation from your point of view?

P.B.: I would see a very simple solution. We do exactly the same on the northern border with Belarus as we do on the southern border with Ukraine. People do not know this, but the Border Guards at the border crossings on the Polish-Belarusian border, have not been accepting asylum applications for a long time. I don't need solutions here. The law provides these solutions. Poland has ratified the Geneva Convention twice. Besides, we have a constitution that prohibits torture and inhumane treatment. Pushbak (read more about Pushbacks and crimes at the border) is a form of torture. It is a fact. All human rights organizations agree here. It doesn't matter how a person got to the territory of Poland, it doesn't matter whether he passed legally or illegally. If there is a person who found himself in the territory of our country and wants to ask for asylum, then the application should be accepted, considered and then it should be decided what to do with that person.

Anyway, we already have 10 judgments of national courts that say that our Border Guard is acting illegally (read more about legal situation), and maybe that's why there are now signals, maybe subtle for now, that at least some guards will reflect a little. There was a letter from the Border Guards to Gazeta Wyborcza, recently there have been no pushbacks from hospitals, for example from the hospital in Hajnówka. Well, for about two months, although this may also be related to the fact that those people who were actually in a very bad shape, with important orthopedic injuries.

E.K.: Well, I also wanted to ask about Border Guards. How do you see their presence and their actions at all? What contact did you have with the authorities?

P.B.: Maybe I'm not a good person to talk about them, because they are so nice to me that it's beyond belief. For example, they pretend not to see me. So I did not experience any situations from the services where they were aggressive towards me. Perhaps it is related to the fact that journalists ask me about it very often. Here, in practically every interview, I answer the same truthfully that the Border Guards never pulled me over, called me names or used violence. On the contrary, once, during the time when there was still a closed zone at the border, I was leaving the zone and I was checked. The man started shouting at me, it was very unpleasant. But then he took my ID, probably checked who I was, and suddenly became nice, wished me a nice day. So I didn't experience any aggressive treatment from the services.

E.K.: It's surprising what you say about the Border Guards, because generally everyone I talk to has a completely different attitude to it and different experiences. However, yes, there are people who say that it happens that someone from Border Guards turns his head away. It happens that refugees say that they got food from someone, but we also hear more and more often that they are treated brutally.

P.B.: Yes they are beaten, here in the Białowieża section it is very, very brutal. I confirm this, from my experience at the border, because I had the opportunity to go even to Lubelskie, because there were also refugees there. Here in the Białowieża section, refugees often report, especially I have the impression that for the last few months, various forms of violence. However, when it comes to the violence of the Border Guards against activists, I think that it simply results from the fact that I am a recognizable person, so I think that the Border Guards will treat, so to speak, anonymous activists differently. They are afraid of the media.

E.K.: I wanted to ask about the work in the forest as a natural environment and the forest as a medical room. Right now it's forest medicine, that's what we call it.

P.B.: To be honest, I'm starting to hate this forest, maybe I have some PTSD. Especially in winter. Although it's not easy in any weather. Working as a medic in the forest is really scary. For various reasons. By the time you get to this patient, you're already tired and sweaty. In order to help a patient in some way, you usually have to take some medical intervention. A person who has hypothermia, if he gets warm liquids he will really recover much faster, or, for example, dehydrated in the forest who has hallucinations. Of course, you can try to give him a drink and we do that too, but fluid therapy is just needed and you need to maintain some hygiene in all this. This is very difficult. Even the mere fact of examining these patients and not attracting anyone's attention, especially at night.

In winter it's dark most of the day, so what we're doing now with Ola (read an interview with her), who I consider to be the main medic at the border, because she comes here for two weeks a month, and that's a lot - she's a midwife and rescuer , so she has a professional education, which I, for example, do not have. So we came up with something that we examine these patients under these sheets, tarp, and under them we put heaters, the ones that break and warm up quickly. So that's cool. These people are undressing. We, in turn, are sweating, we are all wet. In the forest it is also so that you really need to examine this man as soon as possible so as not to draw attention to yourself and be as quiet as possible. You also have to somehow take care of your own safety and we go and come back through the forest without flashlights. I personally consider it a miracle that nothing has happened to any of the volunteers yet, that no one has really broken a leg, broken a spine or suffered other serious injuries. I hate this forest and I hope to go there as rarely as possible. I hate this treatment of people in the woods. I miss a roof over my head, I miss nurses. I miss lighting, everything that is needed and a sense of security.

You know, a young doctor anesthesiologist has been on the border for several days and I saw that she was a little scared because she had a difficult intervention. She didn't do anything wrong, she called an ambulance to a person who was in bed condition and the Border Guards treated her really badly. And that's another thing that's aggravating about this job. I also appear under my own name, although I am already prepared that I can take it on my chest in case of emergency.

I had a long conversation with this anesthesiologist about how to administer these fluids in the forest at all, how to do it so that the drip does not cool down. We considered administering subcutaneous fluids, which is what is done in palliative medicine, because all these punctures are simply very difficult, even in a person in hypothermia, the veins are very sunken. Quickly bringing this man to a better state of health, putting him on his feet in the woods and not in the hospital, is a huge difference for him. If he is put on his feet in the woods, well then he can go on, go where he wants. There is no risk of pushback or deportation at all.

E.K.: What about the mental state of the refugees in the forest?

P.B.: The mental resistance in the forest must be strong enough for a man to get up and go. And here I had various doubts. In the case of women after sexual violence, no woman in the forest confirmed it to me, but I had a few women who were just so stuporous and I saw that they had bruised legs, snakes of blood. They admitted that Belarusians beat them but did not go on to say what happened to them exactly. These women were in shock, they asked for painkillers, wound remedies, disinfectants. What was characteristic was that they also wanted to take care of themselves. Once I had a situation where there was a group from Yemen, a group that kept one woman out of the way, isolated her a bit. In the forest you really have very limited possibilities of action. I adhere to the principle that the refugee decides. The decision may not seem very good, but I believe that it is giving subjectivity to this person. And if, let's say, such a person insists that he is able to go on, he is fine, even though I see that something is wrong with him, I let him decide, I respect their will. There were cases when it was obvious that the mental state was so serious that I had doubts about how they would cope.

E.K.: How do you feel when you walk away from patients and leave them there?

P.B.: The hardest thing for me is to leave children. And it's very difficult for me to leave in situations when I just have doubts or whether I don't really know what the truth is. The situation at the border is a paradise for human traffickers and cooperation with the La Strada foundation is important, there are cases that we consult. The truth is that I am not a specialist in identifying victims of human trafficking. And the most difficult for me are situations when I just don't know if this child in the forest without parents is safe or not. Or, for example, when I meet a child who asks me to take him home, I can't do it. When I leave children in the forest who have been pushed out with their families for several months and I don't know whether they will push them further or not, it is very burdensome. When I leave such people in the forest, that is - I can't even name it, what I feel, but I can say that the mental cost is very high.

E.K.: What do you think about it, about the future? Because nothing seems to change.

P.B.: You know, I guess there's only one way to change that. Namely, the Belarusian side. If they say stop, it'll stop. However, I think that no walls, no wires, no cameras will stop these people. I believe that neither the Polish government nor the Border Guards are particularly interested in ending this crisis. I think if they cared they would have taken other steps. People are crossing over that fence. Admittedly, it happens that they break at the same time, but quite recently two women in the ninth month of pregnancy, just before the beginning of labor, went through. Our services are so incompetent. Let's say we have very incompetent border and military guards, which affects how many people pass through. On the other hand, I believe that our decision-makers do not want this migration crisis to end. I think that our decision-makers received a group of people to scare the society with them, so I think even more that if this is to end, then only if the Belarusian side so decides.

E.K.: From the north of Poland - the Kaliningrad region. There begins another border, where another wall is to be erected. You know, I observe nature and climate change. I believe that this is just the beginning of the migration of people in the world. We really should learn a lot now, learn and prepare for what is going to happen.

P.B.: Of course, I am of the same opinion, because for the time being, we have a miserable 20-30 thousand people on our northern border. Does it matter at all that no one knows exactly how many of these people we have and there are no reliable statistics? Border Guards statistics are unreliable. So people pass through our country. Nobody knows exactly who. No one knows exactly how many there are and no one knows exactly how many times. But let's say we had all these people around 30,000, right? After all, it's nothing.

E.K.: The Ukrainian border has shown that we are able to accept many people. And it is incomprehensible to many people why this is not happening on this border where we look at people who are dying.

P.B.: I just think the answer is racism. It's nothing groundbreaking either, it's just the fact that the world is racist and I often write in my statements that white life will always be more valuable. If not always, it takes many generations to change it. Simply white life is more valuable.

E.K.: It's striking. It's so hard because, in general, none of us choose where we are or what skin color we're born with.

P.B.: I will even say more that, for example, refugees, that is, maybe not refugees now, but, for example, people who have been living in Poland for many years and have citizenship, for example Chechens, are my best friends. And I think that, how to say it, I miss such people in Polish society, so socially useful, those who will always help, so open.

In general, this conference of Minister Kaminski is completely absurd. How can you show a photo from the Internet a few years ago of a man having sex with a cow and say that these are these people? Those thousands of people, even from different countries, from different parts of the world, are Muslims and Christians. And they are all pedophiles, zoophiles? This is actually an incitement to hatred. But you know, just that journalists were at that conference and didn't leave? The fact that they didn't even boycott it, they didn't knock on the head and they didn't even say what nonsense it is, it's incomprehensible to me.

E.K.: Now I am afraid of winter and those frosts, and I also hear what is happening on the Belarusian side, in this death zone, between the barbed wire, with those people whom the army does not want to let go in any direction. From a medical point of view, do you even think a human can function in such temperatures? How long can a person survive?

P.B.: In general, the principle of an hour and four is adopted here, so let's assume there is a kind of average rule, but of course there are many deviations from it. Now most of them have to cross the river. A human being in 4 degree water can survive for an hour. Of course, it also depends on his condition, age, how much he has gone through before or if he ate something warm or not. Here we are dealing with a situation when these people have to cross the river many times, so then, for example, they leave the river and do not change into dry clothes, but continue in the wet ones until we deliver them. However, to be honest, last year we had less, because the Belarusians gathered people in these warehouses in Bruzgi. What I'm most afraid of is spring, to be honest. For me, the worst such moment was the spring of 2022, when the war broke out in Ukraine, the volunteers left there, all this systemic help, i.e. medics at the border, and then PCPR turned up because there were not many medical calls, there were less transitions. People were gathered in warehouses on the Belarusian side, and then these warehouses began to empty rapidly, and this lasted for two or three months. These were the people from the most vulnerable groups, i.e. people with disabilities, families with children, pregnant people, injured people, people with frostbite for amputation with tissue necrosis. For me, it was the worst period and now I'm afraid it will repeat, because those aid organizations that are now have signed contracts until April. I'm afraid that the same situation will happen again, that there will be fewer of these calls in the winter, so that large organizations will come to the conclusion that there is no point in being here. They will leave, and we will again have a lot of this work, the most difficult one. And working with these vulnerable groups is very tiring.

E.K.: We know that Minsk is full of people, on the street and in rented houses. We do not know how many people are in the forest. It's also that they're still coming.

P.B.: So they will definitely want to pass.

E.K.: I got that information. We are not able to confirm it 100% that morgues in Belarus are full of refugees.

P.B.: Refugees have often told me that there are mass graves there in Belarus. Anyway, they told me different things. They told me about dragging bodies before there was a fence, from the Polish side to the Belarusian side. Also, taking into account what is happening in Belarus and the weather we have, it is logical that people will die.

E.K.: How do you deal with it? With all this at a personal level? And what is your life like now?

P.B.: I reorganized my life. However, as I said, since there are now medical organizations involved, to which I am very grateful, my life has simply changed a lot and I think that I have regained it to a large extent. I feel really better than a few months ago, so I would really like for it to stay that way and for these organizations to stay with us, because they are very much needed.

E.K.: A migration route that opens usually never closes. People will still try to go even though it is not an easy road and even more often deadly.

P.B.: I have exactly the same experience. Sometimes, for example, people I don't know contact me, they write to me from Syria. They have no chance of getting any humanitarian visa. They are often sick or have sick children or just want to live. In Syria, you are not able to go to college, because then there is the duty of military service, and military service in Syria is not like in our country, it is a fight against the Syrians. Understandably, they want a normal life in a country where there is no war. I told every person who came in contact with me that if he came here, he would risk losing his life or losing his health. But I've never been able to tell anyone not to do it.

E.K.: Providing humanitarian and medical aid should be the duty of our state, not ours.

P.B.: It is an obligation without a doubt. In practice, the state does not comply, it is the duty for it to comply. It is terrible that people hide the fact that they help with the fact that they do something very good, that is, they help another human being.

E.K.: Don't you feel a bit like you're at war?

P.B.: I think that perhaps the biggest threat is when we already accept it as normal. I remember when I had such a situation with a girl with a dislocated shoulder and there was an army standing three hundred meters away. We were just scared. She begged me to set her shoulder. I explained that I can't, because I've never done it, but she asked and that she took it upon herself, that she simply can't run away with this shoulder. A dislocated shoulder is a very big pain. They've already pushed her out four times. She didn't want to be pushed out again, she wanted to go to the Netherlands, where she has her family. So I called the orthopedic surgeon. I discussed with him how best to do it in this situation. We laid her on her side, put NRC foil under that arm, and me and a friend were pulling her hand, and the other friend was holding her head, making sure she didn't move. If it moved, the head of the joint could go somewhere else at all. We'd make trouble. She was biting a stick wrapped in a glove all the time so as not to scream, because we were very close to the road, and 300 meters from those soldiers. I described it when she was already safe, I described it on social media, and some time later I talked about it with my friend who is a therapist, and she replied: "Paulina, you know, it's like that during the war", and only then I thought to myself: indeed.

E.K.: It's a bit like someone on the side who is from the outside and listens to it, I often tell our stories somewhere, they say that: I feel like I'm in a war, or as if they were talking about a war movie. You're an underground doctor, you don't go with an ambulance siren, where everyone pulls away and helps you. The Border Guards carry the man closer so you don't have to go, you just slide through the woods with a heavy backpack. And in secret. This is war.

P.B.: And somehow I feel it especially when I go home, to people who are hidden in houses, somewhere in a barn or even somewhere in a trailer, or even somewhere in someone's house and all the windows are covered there. And even though it's a house, people talk in such hushed voices. And somehow I feel it the most when some completely random person found someone, or there are such situations, there are not many of them, but they are. People took them home and they are terrified, trembling. I also had a case when someone said who found a family that this family can only be there for two hours and then they have to go. And then I felt like it was the Second World War and hiding Jews in cellars.

E.K.: I think many of us feel that way. We will pay for what touched us. You, as a doctor, should also know that our psyche cannot withstand such a trauma for a long time. Because we are traumatized. We also meet people who are traumatized. What I heard is that at such a moment the traumas of generations are activated. Literally. And we can't start healing the trauma either, because it's still going on.

P.B: This is what our main psychotherapist from my Białystok group says. We are in acute trauma. Protracted acute trauma. All I can say is I hope that maybe one day the state will pay compensation for the loss of mental health.

E.K.: You are also in this activist environment of those people who have been going to these actions practically all the time for a year. Do you see PTSD?

P.B.: Of course. PTSD surrounds us. We breathe PTSD. The zone showed it a lot. What the creators of the zone said, that you who live here on the borderland not only live "ass" in but also arranged in this "ass". And that's one of the worst things I've ever heard. If it ended suddenly, we would have a big problem returning to normal life.

As a supplement to the interview and the events that took place after our conversation, I am enclosing a short explanatory text.

The aid operation in the swamps conducted by Paulina Bownik and activists on January 7, 2023 (I describe it in detail below) was later defined by the Border Guard as “obstructing the rescue operation” which caused that the doctor, who had previously spoken well of the uniformed services, to change her mind and intends to take the slander case to legal action. Such slander for the doctor is a risk of losing the trust of patients and a negative opinion in the professional group.

Below we describe what the rescue operation looked like from her perspective. The entire intervention is supported by photographic, audio and video documentation.

On Saturday, January 7, 2023, volunteers from the Crisis Intervention Point (run by the Catholic Intelligentsia Club) and the Granica Group received information about three Afghan citizens in urgent need of help. People calling for help were in a swampy area near the Siemianówka reservoir. A group of activists set off for the rescue operation, and later, at their request, a doctor, Paulina Bownik, joined them.

The doctor, after a preliminary examination of the situation and providing the initial help possible in the swamps, asked the volunteers to urgently call the emergency number with a request to send an ambulance. Two Afghans were severely hypothermic and required immediate hospitalization. The dispatcher did not initially accept the report. The doctor repeatedly asked for repeated requests for medical assistance. She received information that the Border Guard could not find them and the Fire Department did not even try. The dispatcher of the Crisis Management Center demanded that the services be brought to the scene of the action, which was supposed to be a condition for providing assistance. While it was dangerous for the tired volunteers to split up in the swamps, services were brought to the scene. 30 firefighters, two Border Guard officers, two ambulance crews and six volunteers took part in the operation. People's lives were saved thanks to the cooperation of all participants of the action.

Meanwhile, an entry by the Border Guard appeared on Twitter, accusing activists of... obstructing the operation. The doctor involved in the operation was shocked by the Border Guard's announcement, especially since there is a lot of evidence of what the rescue operation looked like. There was a journalist among the volunteers, there are recordings and recorded conversations with the control room.

Agata Kluczewska, president of the Wolno Nam foundation, founder of the Podlasie Voluntary Humanitarian Rescue, spoke out about the harassment of activists by the Border Guard: "The Guard defamed the activists," Kluczewska says in the recording. Volunteers are considering suing the Border Guard.

We received a medical report from the operation in the swamps from doctor Paulina Bownik. We quote it in full:

"Medical report.

3 men from Afghanistan in the marshes of Siemianówka, on an island under a tree, aged 24-26.

3 men from Afghanistan in the marshes of Siemianówka, on an island under a tree, aged 24-26.

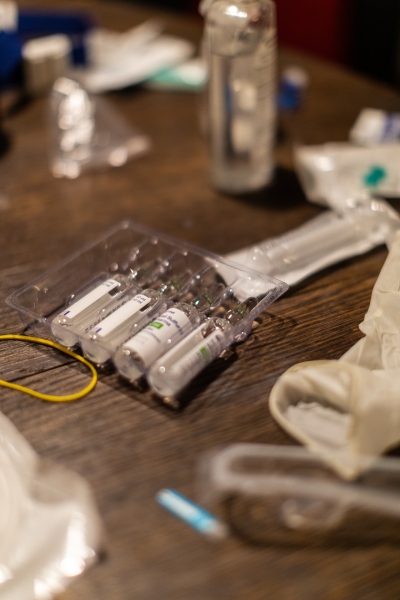

Approx. time. 19.00 On 7.01 I reached patients who were looked after by volunteers from 15.00 - they called a doctor due to the poor general condition of patient 1. The patient with hyperthyroidism (patient 1) was in the worst condition, he had been taking metizol, without medication for several days. Tympanic temperature 34.8 degrees, blood glucose 71 mg%, HGB 16.5, HCT 49%, HR 160-170/min, RR and SpO2 impossible to determine due to temperature (pulse oximeter did not show correct values) and very difficult conditions tests.

The men lay around the trunk, on a patch of earth and a drop down into the icy water, there was no way to undress them for examination.

A man sleeping, in contact, agitated, made uncoordinated movements (after receiving medication), not entirely logical, vomited saliva in front of me twice, mucous membranes very dry, extremely dehydrated, collapsed veins. He received 500 ml of glucose 5% and 1 Amp. Metoclopramide IV. He fell asleep during the administration of medication, woke up in better contact, was able to get up, thanks to which I gained access to the second patient.

Patient 2. Initially, I was only able to measure his temperature on the tympanic membrane - it was 35.08 degrees, the patient logically answered questions (communication in English). While the first patient was being examined and given medication, which took about 2 hours, the second patient slid into the swamp, was knee-deep in water, began to sleep, with almost no contact, the temperature of the eardrum was 33.8 degrees - a decrease in comparison to with an earlier measurement of 2.2 degrees, he did not swallow fluids, also signs of dehydration. I was unable to determine other parameters due to difficult terrain conditions. I gave the patient 250 ml of glucose 5% (all liquids were warm, covered with heaters).

The third patient was hysterical, crying, repeating that his back hurt, begging not to be expelled to Belarus, talking about the violence of the local services, repeating that the Taliban would kill him in Afghanistan, but he was the only one who was able to walk. I was unable to physically examine patient 3 (men in worse condition, patients 1 and 2 kept sliding down the sloping ground into the cold water, we had to hold them, pull them up.) After about 3.5 hours. waiting, other volunteers found us, brought firefighters from TSO Siemianówka and TSO Hajnówka, two more seriously ill patients were carried out of the swamps on stretchers, one was led by a volunteer and a border guard. Due to the very difficult terrain, it took about three hours to get people to the road in Babia Góra, in the last 500 meters firefighters from TSO Lewkowo changed the previous hosts. All patients, after performing rescue operations in ambulances, were transported to the hospital in Hajnówka.The men were not carried out on a stretcher but on a life board, they had been in the forest for three days, drinking water from the swamps.